Legend has it that the two ends of the Channel Tunnel were 50mm apart when the French and English engineers met in the middle. For some, that reinforces the notion that the two countries have never quite seen eye to eye. Compare “English Channel” and the French translation (La Manche or “the Sleeve”). Others disagree, noting that the slight misalignment was safely within planned margins of error, holding up the project as a feat of Anglo-French collaboration.

Either way, the lesson learnt from the tale is that the same structure can be seen differently, with mismatches appearing, when looked at from either side of the Channel. In this bulletin, we will take a look at another structure seen differently through the two national lenses: the usufruct.

What is a usufruct?

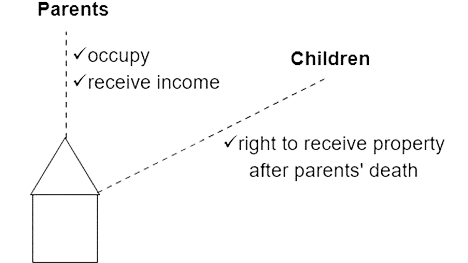

The usufruct is a popular means of owning property in France. The donor gives away the right to receive the property, most commonly, after their own death. During their lifetime, the donor is entitled to live in the property and receive any income. The arrangement also imposes other rights and obligations, which are not covered in this bulletin.

A frequently encountered scenario is below:

Usufructs are often set up in documents entitled Donation Partage (“partial gift”), signed in front of a French notary.

Similar arrangements are often found in Spain, Italy and other civil law countries, but we will focus on the French construct in this bulletin.

Why are usufructs popular?

The main advantage is that when the donor dies, no French inheritance tax is payable at all.

Whilst there is French tax on creating the usufruct, it is lower than would be the case with a simple gift on death. That is because the French civil code sets out discounts based on the donor’s age. The older the donor, the greater the value for tax purposes.

These features mean that the usufruct has become a common tax planning tool in France. However, the tax implications outside of France are not always highlighted to clients, which can cause problems further down the line, if left unchecked.

UK tax issues

Something which surprises many clients is that UK tax needs to be considered with these arrangements.

The main reason is that, in HMRC’s view, a usufruct should be treated for inheritance tax as a life interest trust. HMRC’s view is not legally binding and there is generally no definitive law on how usufructs should be taxed. Whether to follow HMRC’s view should be discussed with your advisor in each case, weighing up the risks and opportunities. However, for the purposes of this bulletin, we will discuss the tax consequences of the “life interest trust” approach.

Before doing so – a further health warning. Not all clients will be affected in the same way, depending on their background. Clients both born and resident outside the UK will be less likely to be affected, but this is only a rule of thumb and the position should always be checked. With that in mind, some of the main issues to consider are set out below.

1. Taxes on setting up the usufruct

A 20% UK inheritance tax charge would apply, by reference to the value above the nil-rate band, currently £325,000.

A mortgage secured on the property can be deducted from the value subject to tax. Depending on the specific circumstances, there may be a good case that the property subject to the charge is not the whole property, but only the value which the donors retain.

The setup of the usufruct will be a capital gains tax event. This means that any increase in value since the donor acquired the property will be charged, often at 28%. The annual tax-free allowance may not be sufficient to fully absorb the chargeable gain.

French tax should normally be deductible, but this will depend on the circumstances.

2. Taxes during ownership

There will be a charge of up to 6% UK inheritance tax on the net value of the whole property every ten years from the date the usufruct was set up. This assumes that the usufruct was made during lifetime.

3. Taxes on death

A pro rata of the 6% ten-year charge discussed above will apply on the death of the donor, if that means that the “trust” for UK inheritance tax comes to an end.

The net property value will be subject to UK inheritance tax as if still owned by the donor personally, generally at 40%. If the property passes to the spouse, no tax applies.

Generally on death, there is a tax-free uplift in the base cost of an asset for capital gains tax, so if the recipient was to sell the property later, they would only pay tax on the gain since the date of death. There is a good case for that to apply, which is in the taxpayer’s favour. Although not entirely clear, HMRC appear to agree.

What should I do if I have a usufruct?

Seek specialist UK tax advice.

Depending on your background, some of the UK tax charges discussed above may not apply, and we can confirm if that is the case.

If required, we can examine the documents (even if in French), set out the relevant law, and liaise with your French advisors, in order to come to a recommendation as to whether HMRC’s view should be followed, or if a different analysis is warranted. It may be the case that a late tax payment needs to be made, and if so, we can correspond with HMRC on your behalf, minimising penalties as far as possible.

We are only qualified to advise on the law of England and Wales. Any references to French or other law are purely our understanding and should be checked with a local advisor.