Partner Natalie Pilagos shares her thoughts on the news that Michael Gove has effectively halted plans to turn the former ITV studios on London’s South Bank into office space by issuing it with a so-called Article 31 notice, published in Building Magazine.

Communities secretary flexes political muscle on 72 Upper Ground, with worries that more developments will be stalled by minister’s decisions

Last week, communities secretary Michael Gove dropped a bit of a bombshell when he effectively halted plans to turn the former ITV studios on London’s South Bank into office space by issuing it with a so-called Article 31 notice.

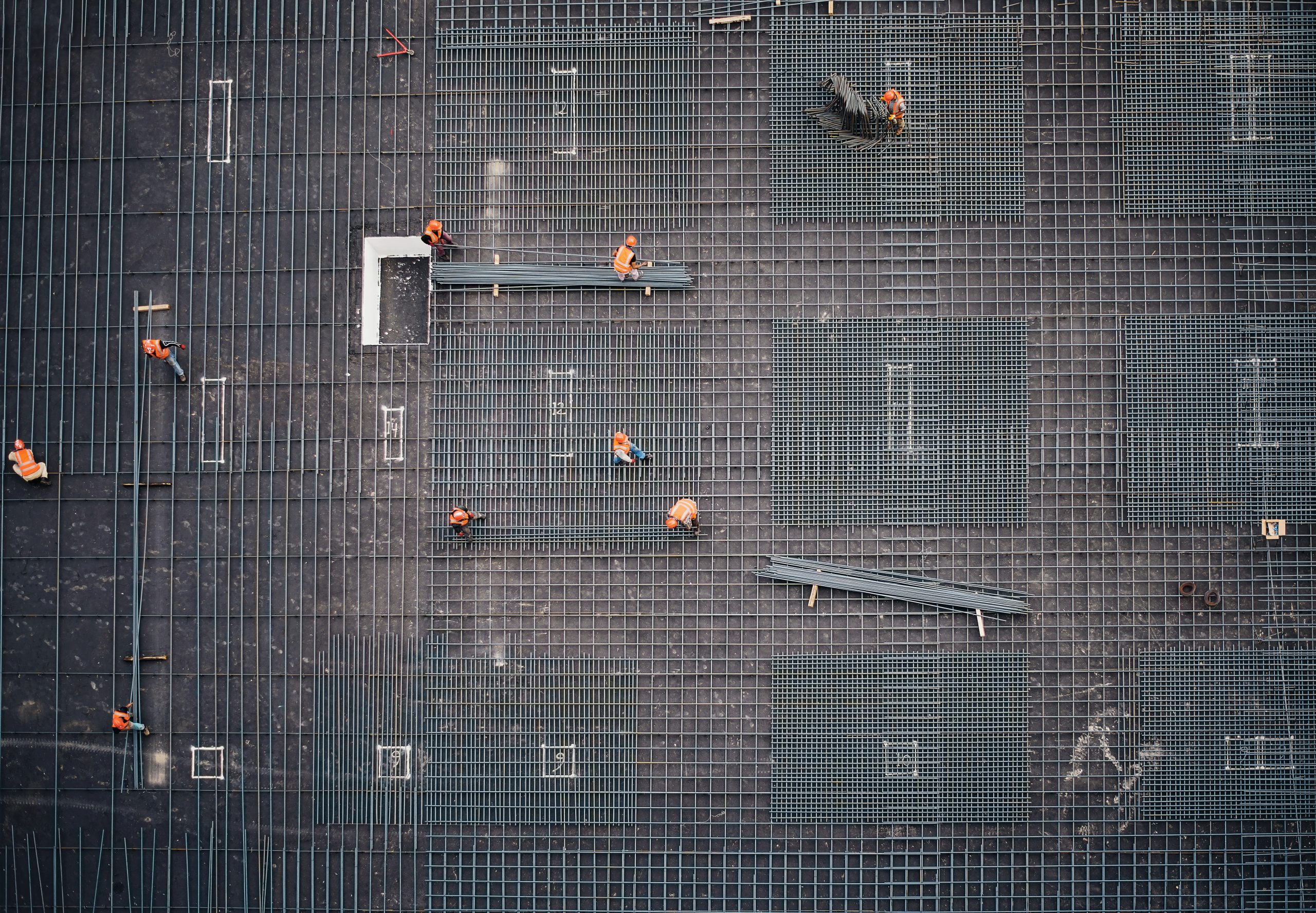

McGee was weeks away from starting demolition work at 72 Upper Ground, originally built in the early 1970s. After beating Sir Robert McAlpine and Laing O’Rourke, Lendlease had just been chosen as contractor and the rubber-stamping process of its appointment was still going on.

In a statement, the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities said Gove was “pausing the application to demolish the former ITV Studios while ministers consider whether it should be ‘called in’. Before ministers will consider whether to call in or not, Lambeth council will refer the application to the Greater London Authority.”

In other words, the job is on ice – for now – and if it does get called in, the consensus is that it would delay the job by a year to 18 months. Teams would have to be stood down and redeployed, schedules redrawn. It would be a headache, to put it politely.

And, of course, being called in leaves it at the mercy of the man who halted it in the first place. Gove would make the final decision.

He shocked some last autumn when he kicked Foster & Partners’ plans for the Tulip, set to be built in the shadow of the Gherkin, into touch once and for all. Some members of the Tulip team Building spoke to in the weeks before last November’s verdict were confident enough to suggest the decision would go their way.

But Gove thought otherwise and said turning it down was in part to do with the quality of the architecture, which he did not rate, and the amount of carbon that would be used in a structure more than 300m high.

The man who likes to say ‘no’

A former Building columnist, Gove has had more brushes with the built environment than several of his predecessors. He took aim at architects more than a decade ago when he scrapped the Building Schools for the Future initiative, claiming the profession was “creaming off cash”. More recently, he has pursued housebuilders much more vigorously than the man he replaced, Robert Jenrick, for their share of costs to fix dangerous cladding. He has taken a tough line with products manufacturers as well, warning them of “reputational” consequences if they, too, don’t pay up.

And last month, he paused plans by the country’s best-known retailer to knock down its flagship store and replace it with a 10-storey block. No official reason has been given but the amount of carbon Marks & Spencer’s scheme on London’s Oxford Street will regenerate is thought to be at the heart of the matter. Like the team behind 72 Upper Ground, M&S is now sweating on what the communities secretary decides to do next.

There is now a growing wariness in the industry that these interventions will not be one-offs. It’s spooked some and left others to wonder which project is next. “It’s too early to comment,” veteran developer Sir Stuart Lipton admits. “I need to understand what the new rules are.”

“I am not surprised that developers are worried when they have been working on projects for years only to find the rules have changed,” says Peter Murray, chairman of architecture thinktank New London Architecture. “I’m of the view that we need to move to a greater focus on retrofit. However, sudden shifts in policy like this are not good for London.”

There are largely two schools of thought as to why 72 Upper Ground has been paused: Gove either does not like the design and has taken note of a well-organised and vociferous local campaign against it; or, in an age of carbon reduction targets, he has concerns that developers are still going for a “knock it down and rebuild” strategy first.

“I think we will definitely see more of this going forward where he [Gove] will come along and go ‘hang on, have you considered this, this and this?’,” one developer says.

Others, too, are expecting to see more interventions by ministers in the future. “It is fair to say that it is our expectation that any new tall buildings will be looked at very carefully post Grenfell,” says Natalie Pilagos, a construction partner at City law firm Wedlake Bell.

The carbon agenda

Designed by Make Architects, 72 Upper Ground includes a 26-storey tower and smaller 13-storey block. Opponents say the scheme would be 225% the size of the current ITV tower.

Pilagos adds: “The environmental impact of the construction process also needs to be considered to a much greater extent than it is now. I think sometimes developers think they can knock down what is there and start again, which is often cheaper than a refurb, but has more of a carbon footprint.”

One source familiar with 72 Upper Ground says nothing can be done with the existing building. “I know the team looked very hard at it. But sometimes you have to start again.”

Mark Cleverly, head of property and construction in the south for CPC Project Services, thinks the issues at 72 Upper Ground are both local and national. “It appears to me, on the face of it, that perhaps the stop placed on that project might be as much to do with the scale of development proposed within the townscape at that location as well as the concerns about carbon.”

But Cleverly says sustainability issues are coming more and more to the fore – although he adds that the days of developers reaching for the wrecking ball first are gone and, in any case, not all buildings can be saved and reused.

“The London development sector has delivered some fantastic and leading examples of retrofitting and re-imagining existing buildings, saving thousands of tonnes of carbon in the process,” he says. “There are concerns, however, for developers that retaining existing buildings may not be the optimum solution in every instance. Occupiers and tenants, for example, may not wish to occupy what might be considered as compromised space.”

One QS agrees that developers are much mM&Sore in step with the carbon agenda than previously. “Before, the issues for developers were time, construction, quality. Now it’s time, construction, quality and carbon. Our clients are really very tuned into this.”

Still, developers sat on big schemes will be feeling a little more nervous now. “The capital needs to attract investors if it is to continue supporting the UK economy and the secretary of state needs to provide greater clarity of intentions if development is not to grind to a halt,” says the NLA’s Murray.

One developer admits: “If you pop up with a tower, you put yourself on the radar. The next tower that’s going to come along in the City could get the same treatment, that’s the fear.”

Calls for a rethink

With 72 Upper Ground, there is no doubt it is deeply unpopular with locals. Ahead of the planning decision in March, a local pressure group, Coin Street Community Builders, told Lambeth council it had serious concerns about the proposals drawn up for investor Mitsubishi and development manager CO-RE.

These included “the scale, bulk and siting of the proposed development [which] is excessive, overbearing and overly dominant” while worries were also raised about the impact on daylight.

In all, the plans received more than 250 objections and even the planning officer’s report, recommending the scheme for approval, was forced to admit it was “controversial and extremely unpopular”.

The local MP, Florence Eshalomi, called for a rethink, while concerns were raised by Historic England and the Twentieth Century Society.

A spokesperson for 72 Upper Ground said: “Our proposals to transform a dormant, closed-off central London site into a new mixed-use development that prioritises high-quality workspace and the provision of new arts and cultural space will be a great addition to the South Bank.

“It will bring investment, 4,000 new jobs, and new workspace to one of London’s most famous destinations.”

But Coin Street was having none of it and told the council: “The claimed ‘public’ benefits of the development, its expansive views and generous planted terraces, would only be enjoyed by its occupants. These do not justify the harm it will cause to the South Bank conservation area.”

Even some in the industry are not convinced by the proposals. “What they’ve designed there [at 72 Upper Ground] is unnecessary. What is that bringing to the community apart from blocking the river?” one source told Building.

Whatever the reasons, the industry is watching to see what happens. Cleverly says regional developers might start to get worried, with Gove looking beyond the confines of the capital.

He adds: “There is a risk that the private sector will now shy away from investing in regenerating more difficult sites with a longer-term decline in our civic realm and economic output. What decision-making tools and evaluation kits will be used to balance these types of decisions in the future?”

Wedlake Bell’s Pilagos says Gove’s move to pull the plug on the Tulip was the warning shot. “[It showed] the political appetite is not there to push big development through as may have been the case if it does not tick the right environmental and safety boxes.”

For those working on the job there is a more immediate concern. Gove, clearly, has signalled he is unhappy about something. “He is letting developers know he won’t be afraid to intervene on issues of design and carbon and so on,” says one developer. “It puts them on notice.”

To read the original article please click here.